Personal reflections on the Wales Coast Path

The threads that bind personal involvement and interest to academic inquiry can seem like a spider’s web: ghostly, gossamer-thin, hard to trace. Even so, they are definitely there. Why else would you decide to spend months, even years, researching any topic when you don’t have to – when you could have chosen another?

It’s the same with my own work on ‘In All Our Footsteps’, and the long-distance walking on which I chose to spend some of my spare time. I recently walked another long stretch of the Wales Coast Path, from Burry Port to Stackpole Quay in South-West Wales. It might be thought a busman’s holiday, if only there were a few more buses.

There is, however, no real need to try to separate the two arenas, just as the attempt to train the personal pronoun, the ‘I’ in the individual, out of undergraduate writing is probably wrong-headed – as well as futile. Anyone’s private hinterland and professional foreground can and should work together in two directions, with each enriching the other. As my editor said to me when I was a journalist: ‘write what you see, and what you can see’.

That dialogue is not without wry reflection, or a certain dark humour. Forgetting your worries and aches and pains on the trail is a familiar trope: one thinks, for instance, of David Lodge’s novel Therapy, in which the middle-aged sitcom writer Laurence Passmore lifts himself out of depression (and a troublesome knee) by walking on the Camino de Santiago. It’s not so much that one’s reflection while walking ranges vaguely far afield: it’s that it might hit rather too close to home.

One also has to accept a central irony: that of leading a project about the intimate landscape, used by all, which should be accessible to all as of right, while walking on a vast trail, of cinematic scope and drama, with boots and backpack on – a white man in a green landscape just like on the cover of any tourist guide (though perhaps without quite the beaming sheen of outdoorsy fitness). Striding out and moving quickly under a vast sky and next to a huge seascape, I was constantly reminded of the vast majority of our Rights of Way, running thinly through undergrowth, curving between hills, joining up village and town - not the same thing at all, but revealed by contrast as well as experience.

One reason why it’s still good to walk one’s work, as well as think it, is that it is full of what one might call – in the academic jargon – ‘embodied physicality’. It’s all very well scrutinising a map in an archive or at home, or driving parallel to the Coast Path in a car or bus: but the topography is real, in interaction with the body, and that matters. Carrying a few extra pounds after Covid; getting older; having a bad back: these are all held very closely as they affect you, but as you slog along with a goal – in the heat and dust – they are also forgotten. Both person and path are real, but also felt and seen as there in relation to and connection with the other. Lodge’s Therapy is just one rueful account.

Three castles on the route: Llansteffan, Laugharne and Manorbier. Photos: Glen O’Hara.

Then there are the historical reflections as you pass through a multi-layered landscape, one sprawling in time from Victorian pleasure grounds of Tenby to the ex-military bases that now form Pembrey Country Park and the current military landscape around the Manorbier Air Defence Range, from Second World War pillboxes to the modernity of Pembrey’s dry ski slope and toboggan run, and all the way back to the Norman fortresses of Llansteffan and Laugharne Castles (where Owain Glyndŵr's revolt began) and Manorbier Castle, now site of the usual tourist café. It’s hard to believe that one can understand this human landscape without actually trudging next to its hallmarks, seeing where the castles for instance sit amidst the topography - by estuaries, on promontories, guarding key trading routes and dominating the landscape.

The built environment comes all the way up to the present, and stretches forward to the future – indeed, all the way through to the Ballardian post-modernity of the Dylan Coastal Resort, incongruously looming next to the relative modesty of Dylan Thomas’ writing haunts at Laugharne – which brought to mind the luxury private lodges I once noticed near the hostels that house most people on the Routeburn Track in New Zealand.

The Wales Coast Path, these days and like most such routes, is also integrated with online space: witness all the QR codes on waymarkers all along the trail. All of them are portals to webpages about the same overlapping natural and human pasts one can see in the landscape as you walk, just with your own eyes, but now informed – perhaps bombarded – by the ideas of others. Lists of websites abound too, for instance on individual trails’ labels such as those at Pembrey. Many paths are now surrounded by a virtual bubblewrap of information and interpretation: something else that’s hard to grasp in the library.

Postmodernity and the online trail: the Dylan resort at Laugharne; the QR code route at Pembrey. Photos: Glen O’Hara.

The interplay between the natural and the human also has to be observed in person to be understood. The hallmarks of teeming animal life, as well as the life of the wider landscape, were plain to see: what looked like dead smooth hound sharks on the beach; the cows on the path; the eroded and collapsing shore itself, covered by warning signs to prove it; the glittering sea itself; the estuary (of the Taf), a huge obstacle that took a day to walk around. But all of that had to be juxtaposed with traces of the human – the city of Carmarthen, with its modernist local government buildings; the pock-marked concrete of a D-Day training and practice site; the holiday parks and static caravans… and at least one microbrewery, full of Escher-like pipes and wires and tanks.

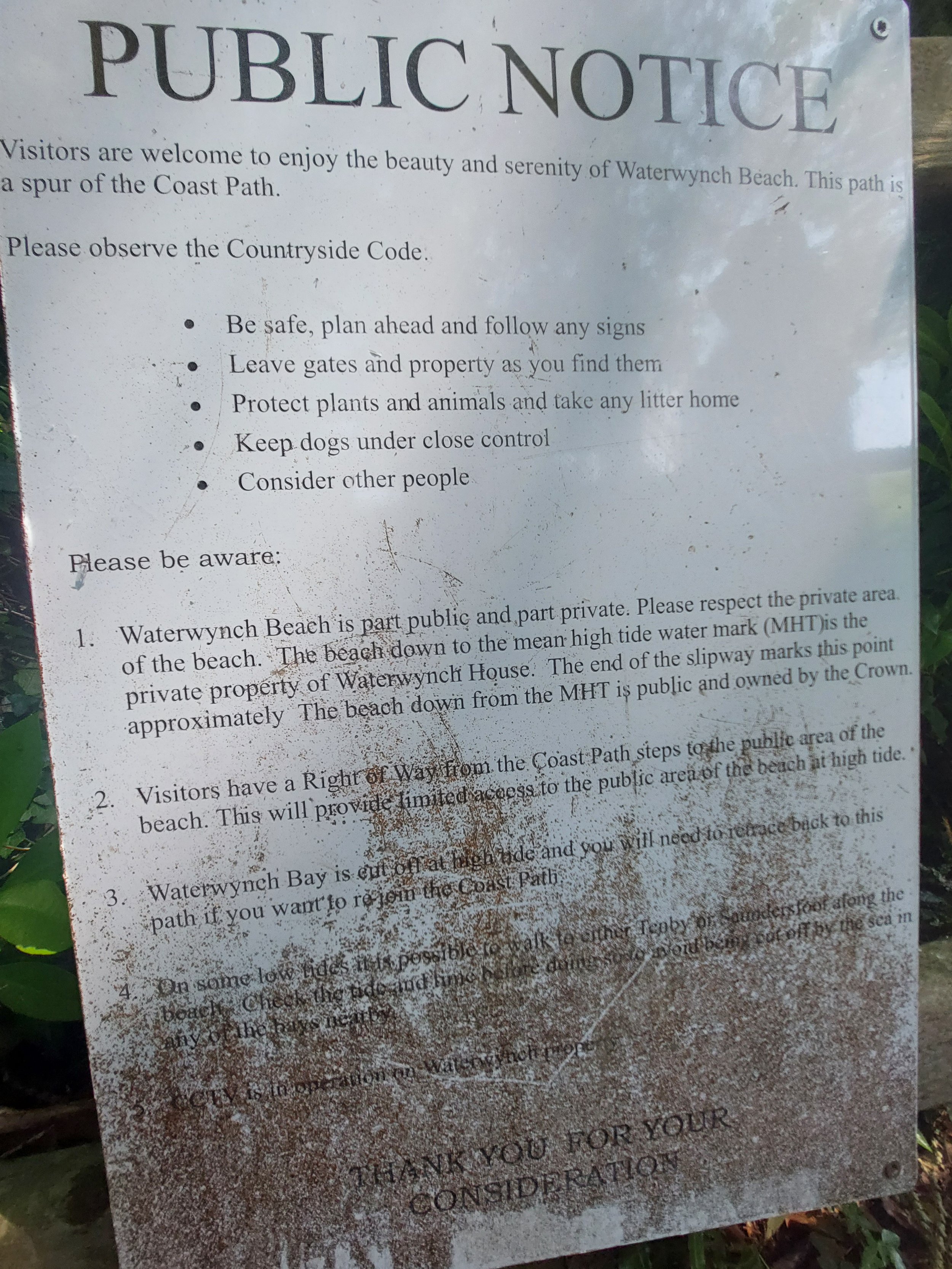

Deep and ongoing tensions between landowners and the wider public were also evident, with many signs trying to hold walkers to their exact path: at Waterwynch Beach, an officious text stipulated that you had to walk directly and strictly from the Coast Path steps direct to the Mean High Tide mark; at one point there was a campsite, and then an allotment, with the 3m wide Right of Way marked out very clearly, indeed it felt aggressively, first in wooden poles and then with a fence topped with yellow boxes to mark the Coast Path. Just after the Manorbier Air Defence Range the signs to your right, as you head West, are very clear: ‘private land; no public Right of Way; please keep out’ (in Welsh as well as English)

Keep to the way: making sure that public access stays where it should be. Photos: Glen O’Hara.

Then there’s the mythmaking involved in the creation of any new ‘way’, including the Wales Coast Path – which is only just over a decade old in its present incarnation. ‘Paths’ don’t really exist – they take shape only somewhere between legal, political and historical meaning and physical reality – and therefore lend themselves to continued reflection on all our myths as we go.

The Wales Coast Path in fact involves long stretches of concrete and suburb, as well as walking next to busy main roads, to join up the more ‘picturesque’ and more open stretches tracking the actual coast. You don’t see that, either, in just the archive. It is a ‘myth’ – an unrolling story – and that’s only clear judged slowly, ploddingly – whether you walk long stretches of the Coast Path, or wheel, ride or walk your circular way from and to a car park.

That’s especially obvious when you see the way in which the coloured lines on your map really work: all mud, or paving stone, or gravel, just the same, perhaps in many theoretical layers as the planner looks at them, rather than actually looking different.

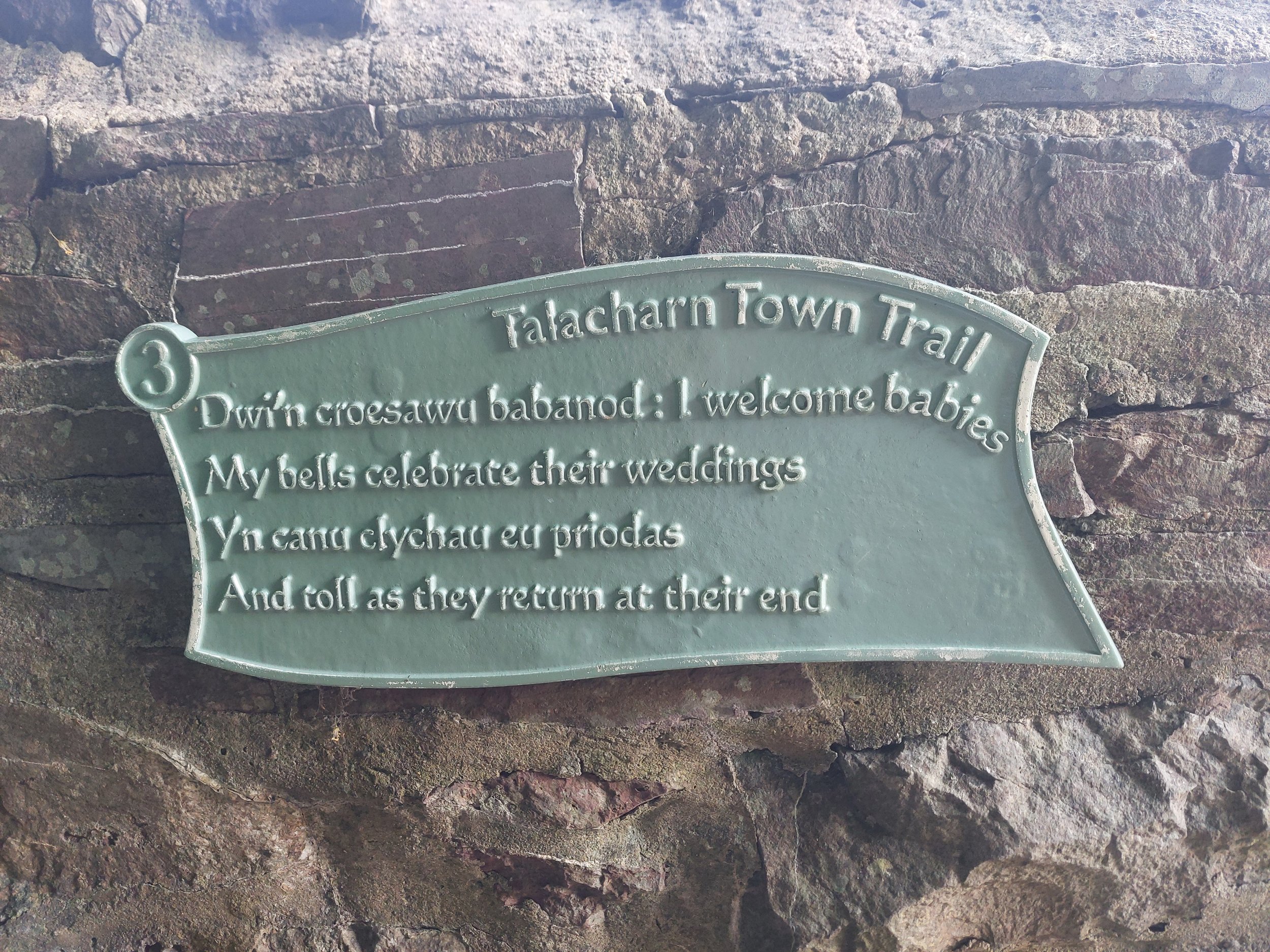

As it wound its way through south Wales, the Coast Path joined, left, intersected with and was carried by other tracks: the Millennium Coastal path from Loughor through Llanelli to Burry Port and Pembrey; The Pilgrim Trail; the Talacharn Town Trail; and Dylan’s Birthday Walk (for Dylan Thomas). One key moment was starting up again with the National Trails acorn that appears once you head into Pembrokeshire and hit the Pembrokeshire Coast Path: an old friend from the Hadrian’s Wall Path and the South West Coast Path.

Where many paths meet: the Wales Coast Path intersects with other ways and trails - of all sorts - all the time. Photos: Glen O’Hara.

That’s just one example of the many, many signs you pass and use on the Path. Some are in the traditional blue and yellow of the Wales Coast Path, often topped with a yellow box, but others are clearer turquoise signs with mileages on them. There are many more: wooden fingerposts with a WCP badge on the main upright; new wooden posts with symbols, not writing, on them from the start, and pointing in more than one direction; yellow footpath arrows with a walking person in stark black on them; Pembrokeshire County Council footpath labels in green and yellow; even one for the English and Welsh parts of the International Appalachian Trail.

Many signs… with many meanings. Photos: Glen O’Hara.

On the surface, such walks are ‘just’ a holiday, and therefore full of cliches – ‘bracing’, ‘bright’, ‘healthy’ and ‘fun’. But the real meaning of the Coast Path went much deeper than that, a realisation that did not overshadow but rather deepened the experience.

The path was and is a physical, mental and emotional landscape in constant dialogue: of pasts with futures, paths with trails, tracks, byways and townscapes; the personal with the regional and national; body and mind; land with sea; ‘nature’ with the human; public space with private ownership.

Understanding that was yet another demonstration of the potential benefits of bringing pastimes alongside work, leisure into line with labour, and fusing physical and academic toil.