Seeing like a quarryman: an unfamiliar ‘archive of the feet’ along Hadrian’s Wall

Last year I walked along the middle section of Hadrian’s Wall Path, a National Trail that opened in 2003 and follows the line of the Roman Wall for 84 miles coast to coast, between Wallsend in the east and Bowness-on-Solway in the west. Beginning at the Roman fort Vercovicium (Housesteads), I set out for Cawfields Quarry, just over 5 miles away. I walked westwards into the prevailing wind, but the reward was a feeling of authenticity in the knowledge that I was proceeding in the same direction as the Romans when they constructed their northern frontier from 122 AD.

This is a spectacular stretch of countryside and, unsurprisingly, it is very popular with walkers. The landscape is green and undulating, and the rocky path is lined with ferns and grass. The footpath generally stays close to the spine-like stone grey wall, and every now and then craggy outcrops descend steeply just to its north. Aside from field walls, farmhouses, and the Sycamore Gap – a sharp dip in the wall that, until recently, framed the tree made famous by its appearance in the Hollywood film Robin Hood and the Prince of Thieves – the features of the landscape seem distinctively Roman. To the south, running parallel to the footpath, is the military road and an additional defensive earthwork called the Vallum. At regular intervals the wall itself is dotted with turrets and milecastles that draw the walker’s gaze northwards, in the same way (we like to think) Roman soldiers looked for signs of barbarian activity beyond the Empire’s northern frontier.

Walking along the wall has long been appreciated as an immersive and embodied route to historical knowledge. In 1801, shortly before his 78th birthday, the paper merchant and bookseller William Hutton took this to the extreme when he walked from Birmingham to Carlisle, along Hadrian’s Wall to Newcastle upon Tyne, before doubling back to Birmingham to complete the 601-mile round trip that informed his History of the Roman Wall (1802). As Paul Readman has shown, walking remained an important means of historical imagination in the twentieth century, an act that the archaeologist R. G. Collingwood described as using ‘the entire perceptible here-and-now as evidence for the entire past’.[1] The historian G. M. Trevelyan also firmly believed in walking as method because it ignited his historical imagination and gave him access to the traces of the past that resided not in texts and archives but in the landscape itself. As Trevelyan put it, walking in Northumberland afforded him insight into ‘the procession of long primeval ages’ that were written into the landscape in ‘tribal mounds and Roman camps and Border towers’.[2] In his book Landscape and Memory (1995) Simon Schama described the process of acquiring a deep sense of place as entering the ‘archive of the feet’, an elegant term borrowed from his former schoolteacher, and which has entered general usage among historians interested in going beyond conventional textual archival material in their pursuit of historical understanding.[3]

Passing through Milecastle 42, the wall ascends steeply to what looks like yet another summit in the endlessly bumpy landscape, before abruptly disappearing. The ribboned contour of the wall has been cut, mid-wave, by a vertical cliff face. This is a sharp and unmistakable disruption in the continuous westward roll of the land, and it also interrupts the walker’s historical imagination. At this point, the footpath leaves the wall to skirt round the edge of a tree-shaded lake, the wall still nowhere to be seen. At the western edge of the water, a Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage Site information board explains that here, at Cawfields, a quarry ‘destroyed Hadrian’s Wall by removing the scarp face of the Whin Sill’. The Whin Sill is an escarpment that offered a strategic vantage point for the Roman frontier wall, and from the nineteenth century the easily accessible whinstone was quarried because it made excellent material for road building. An illustration of the old quarry site gives a sense of the scale of the operation that disrupted ‘such an important archaeological site’. The lake is in fact the submerged quarry floor, sunk as a cost-effective means of making the area more aesthetically appealing to walkers once the quarry workings had been successfully halted.

Hadrian's Wall and Cawfields Quarry from Milecastle 42 (photograph by the author).

Cawfields Quarry in the 1930s (courtesy of the National Mining Museum Scotland. Copyright unknown).

The approach to Cawfields Quarry by the Hadrian’s Wall Path is an excellent example of the capacity of footpaths to shape our historical understanding.[4] In this case, Cawfields Quarry is encountered as a vast hole and an abrupt disruption in the landscape, interrupting the continuity of Hadrian’s Wall as a long, coherent, linear Roman monument. In 1930, this landscape was threatened by the proposal to open a new quarry between the wall and the Vallum a few miles away, near Melkridge. The proposal drew widespread attention to the existing quarries at Cawfields and nearby Greenhead, which were both situated on the line of Hadrian’s Wall. A public campaign was launched to save the wall from quarrying altogether, and on 16 April Trevelyan wrote a letter to The Times warning that continued destruction of the nation’s ‘noblest historical monument’ would be ‘a disgrace to England’.[5] A couple of weeks later, Collingwood and other Oxford University members signed a letter to The Times protesting the ‘disfigurement’ and ‘destruction’ wrought by quarrying.[6] Anyone who spoke out in favour of the quarrying operations was accused of being anti-historical, and of condoning irreparable damage to the countryside that was tantamount to vandalism.[7] From this perspective, Hadrian’s Wall was the defining feature of the landscape, and this way of seeing has been replicated by historians who have focused their attention on the individuals and groups who secured the preservation of the Wall and its surroundings in the atmospheric and aesthetically treasured central rural sections.[8] The result is that we have a detailed knowledge of the campaign to save Hadrian’s Wall but limited understanding of the landscape and its history.

However, by re-entering the archive of the feet by a new route, our experience of the landscape is transformed in a way that opens the historian’s ears to voices that are silenced along the Hadrian’s Wall Path. The new route approaches Cawfields Quarry not from the east or the west but from Haltwhistle to the south. Beginning at the edge of the town, Haltwhistle Burn Footpath runs along the lower section of what was once a narrow-gauge railway line connecting Cawfields Quarry with the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway from 1905 until the late-1930s. Passing the old pipe and brick works, the site of the former South Tyne Colliery and numerous chimneys, as well as the remains of two woollen mills, old quarries and lime kilns along a route that was once a commute for quarry workers, the pedestrian arrives at the site of the former Cawfields Quarry, which emerges as a natural extension of the rural-industrial landscape.

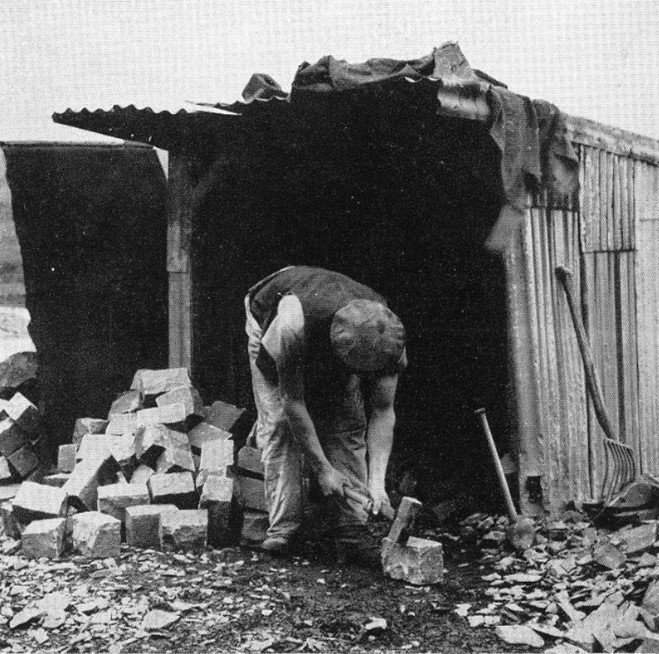

Above: The remains of industry along Haltwhistle Burn. Below left, Cawfields Quarry site today (photographs by the author). Below right: a sett maker at work (courtesy of the National Mining Museum Scotland. Copyright unknown).

This has two effects. Firstly, from this new perspective the landscape ceases to be exclusively Roman in character; no longer frozen in Hadrianic time. The crumbling industrial heritage is evidence of a landscape lived and worked in for centuries after the Romans left, which brings with it the realisation that it was so long before the Romans arrived, too. Moreover, quarries no longer seem like anti-historical forces of destruction. On the contrary, following the stone quarried in this area allows us to trace some of the major contours of British history, from the stones used to build Hadrian’s Wall to those used in the construction of nearby Hexham Abbey in the seventh century, as Christianity spread through the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. After the Norman Conquest, the twelfth century proliferation of stone buildings can be seen at Lanercost Priory and Thirlwall Castle, and in response to the Jacobite rising (1745-6) the Military Road was built between Newcastle and Carlisle, using parts of Hadrian’s Wall for the foundation. The late-eighteenth century spike in demand for quarried limestone (used as a soil improver) was connected to the need for greater yields in response to land enclosure and the Napoleonic Wars.[9] In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, quarries produced stone, aggregates, and mortar that supported the rapid growth of urban centres and helped build a transport network of railways, roads, viaducts, and harbours. Whinstone from the quarries at Cawfields and Greenhead provided material for the RAF Depot near Harker Bridge (1941), the Ministry of Supply’s Missile Test Centre at Spadeadam (from 1956), for runways, slabs, kerbstones, paving setts, and various highways including part of the M6 motorway near Penrith (opened in 1958), as well as for the Atomic Energy Authority’s nuclear site at Sellafield. The transformations of the British economy and society have their foundations in quarried stone, and the landscape as experienced along the Haltwhistle Burn Footpath no longer strikes the observer simply as a site of leisure to be looked upon for its aesthetic value and understood in exclusively Roman terms. The history of the landscape as told by the Hadrian’s Wall Path and its heritage boards seems flattened and homogenised as a result, and the Roman presence in this place is instead understood as one part of a richer, deeper history.

Secondly, experiencing this new and unfamiliar archive of the feet can make us more attuned to the voices of the people who lived near and worked in the quarries before they closed, and their side of the story forms the basis of my recent publication ‘Seeing like a quarryman’.[10] This approach allows us to revisit the quarrying controversy that began in 1930 and rethink some of the assumptions that shape our current understanding of this historical episode, which is widely considered a success story of preservation.

One of the assumptions, alluded to earlier, is that support for the continued working of the quarries was anti-historical, and either ignorant or at least dismissive of the Roman past. On the contrary, many of the arguments put forward in favour of the quarries were in fact deeply historical. For instance, with the quarrying debate raging amidst the urgent need for stone during the Second World War, a letter in the Newcastle Journal signed ‘M. B.’ suggested that:

‘In view of the great shortage of building material for houses for the living, may I suggest the whole of the ancient tyrants’ wall be used for this purpose?’[11]

Just over a week later, another letter described the wall as ‘standing evidence of Roman aggression and British slavery’.[12] Far from anti-historical, the description of the Romans as tyrants and of the British as slaves suggests that those speaking out in favour of the quarries identified with the subjects of Roman imperialism rather than with those who implemented it. This was out of step with the prevailing classical scholarship of the day which, written at a time of British imperial might, tended to glorify the civilising benefits of Roman rule. The understanding of Roman imperialism articulated in the letters seems more in keeping with David Mattingly’s An Imperial Possession (2006), a history of Roman Britain that is attentive to defeat, subjugation, exploitation, resistance, and the dark side of the imperial project.[13]

Another assumption is that the quarries were destructive forces in the landscape that threatened to disfigure rural England. But we can also begin to question this claim by listening to the words of Mr. J. C. Jeffers, a Greenhead resident who gave evidence on behalf of the village and parish council during a public inquiry to decide the fate of the local quarry in 1960. Jeffers explained that the quarry employed over half the men in the village, and it would be ‘a major disaster if it ceased working’ because it would lead to the death of the community. Jeffers concluded:

‘Of course there are people who would gladly close all the villages and concentrate people in larger communities – such a shocking idea, the villages are the flower of the country and I feel sure that the men who form the Society to preserve the Roman Wall will also be the men who wish to preserve Rural England’.[14]

For Jeffers and many like him, quarries, collieries, and other industries were inseparable from the rural landscapes that gave rise to them and the rural-industrial communities they supported. This was a different vision of the English countryside in which the rural and industrial overlapped, and where the landscape was economic and dynamic as well as aesthetic and historic. From this perspective, preservation orders and the growing number of scheduled ancient monuments were agents of change, freezing what always had been working and living landscapes.

Today, the two footpaths leading to Cawfields Quarry reflect incompatible visions of landscape that clashed during the quarrying debates. As historians turn back towards place-based methodologies, we must remain conscious of the paths we tread and the narratives of place they lead us to. In this case, entering an unfamiliar archive of the feet along Haltwhistle Burn Footpath demonstrates the potential of walking as a route to fresh historical insight, as it obliges us to recast the success story of preservation along Hadrian’s Wall as a more complex and uncomfortable social history of landscape transformation, involving preservation but also conflict, compromise, and loss.

Gareth Roddy is a Lecturer in Modern British and Irish History at Northumbria University. He works on the cultural and environmental history of landscape, with particular interest in borders, peripheries, and the histories of travel and tourism. The archival research for this project was supported by a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship and is published in the edited collection Linda M. Ross, Katrina Navickas, Ben Anderson, and Matthew Kelly (eds), New Lives, New Landscapes Revisited: Rural Modernity in Britain (Oxford, 2023).".

[1] R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford, 1946), p. 247, quoted in Paul Readman, ‘Walking, and Knowing the Past: Antiquaries, Pedestrianism and Historical Practice in Modern Britain’, History, vol. 107 no. 374 (2021), 51-73, at p. 73.

[2] G. M. Trevelyan, Clio, A Muse and Other Essays (London, 1913), p. 154. Trevelyan’s method is discussed in David Gange, ‘Retracing Trevelyan? Historical practice and the archive of the feet’, Green Letters, vol. 21, no. 3 (2017), 246-61.

[3] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (London, 1995), p. 24.

[4] Clare Hickman and Glen O’Hara, ‘Delineating the Landscape: Planning, Mapping and the Historic Imaginings of Rights of Way in Twentieth-Century England and Wales’, in Daniel Svensson, Katarina Saltzman, Sverker Sörlin (eds), Pathways: Exploring the Routes of a Movement Heritage (Oxford, 2022), pp. 56-73.

[5] ‘Hadrian’s Wall. Dignity and beauty unregarded’, The Times, 16 April 1930, p. 15.

[6] ‘Hadrian’s Wall. An appeal from Oxford University’, The Times, 3 May 1930, p. 8.

[7] For a contemporary example, see ‘Letters to the Editor. Wall “intolerance”’, Newcastle Journal, 9 September 1943, p. 2.

[8] For example: John Charlton, ‘Saving the Wall: quarries and conservation’, Archaeologia Aeliana, 5.33 (2004), 5-8; Lindsay Allason-Jones and Frances McIntosh, ‘The Wall, A Plan and the Ancient Monuments Acts’, Museum Notes (2011), 267-76; Alison Ewin, Hadrian’s Wall: A Social and Cultural History (Lancaster, 2000); Matthew Symonds, Hadrian’s Wall: Creating Division (London, 2020), pp. 151-4; Richard Hingley, Hadrian’s Wall: A Life (Oxford, 2012); Stephen Leach and Alan Whitworth, Saving the Wall: The Conservation of Hadrian’s Wall 1746-1987 (Stroud, Amberley, 2011); Jim Crow, Housesteads: A Fort and Garrison on Hadrian’s Wall (Stroud, 2004), pp. 137-40.

[9] Kathleen Emily Ann O’Donnell, ‘Quarries of Hadrian’s Wall: Materials and logistics of a large-scale imperial building project’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2020), pp. 58-82.

[10] Gareth Roddy, ‘Seeing like Quarryman: Landscape, Quarrying, and Competing Visions of Rural England along Hadrian’s Wall, 1930-1960’, in Linda M. Ross, Katrina Navickas, Ben Anderson, and Matthew Kelly (eds), New Lives, New Landscapes Revisited: Modernity in Rural Britain (Oxford, 2023), pp. 61-91.

[11] ‘Letters to the editor. Wall controversy’, Newcastle Journal, 7 September 1943, p. 2.

[12] ‘Letters to the Editor. “Wall” Battle’, Newcastle Journal, 15 September 1943, p. 2.

[13] David Mattingly, An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, 54 BC-AD 409 (London, 2006).

[14] ‘Greenhead Parish’ [document 6: proof of evidence given by Mr Jeffers], TNA HLG 89/855.